[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

In short

The challenge

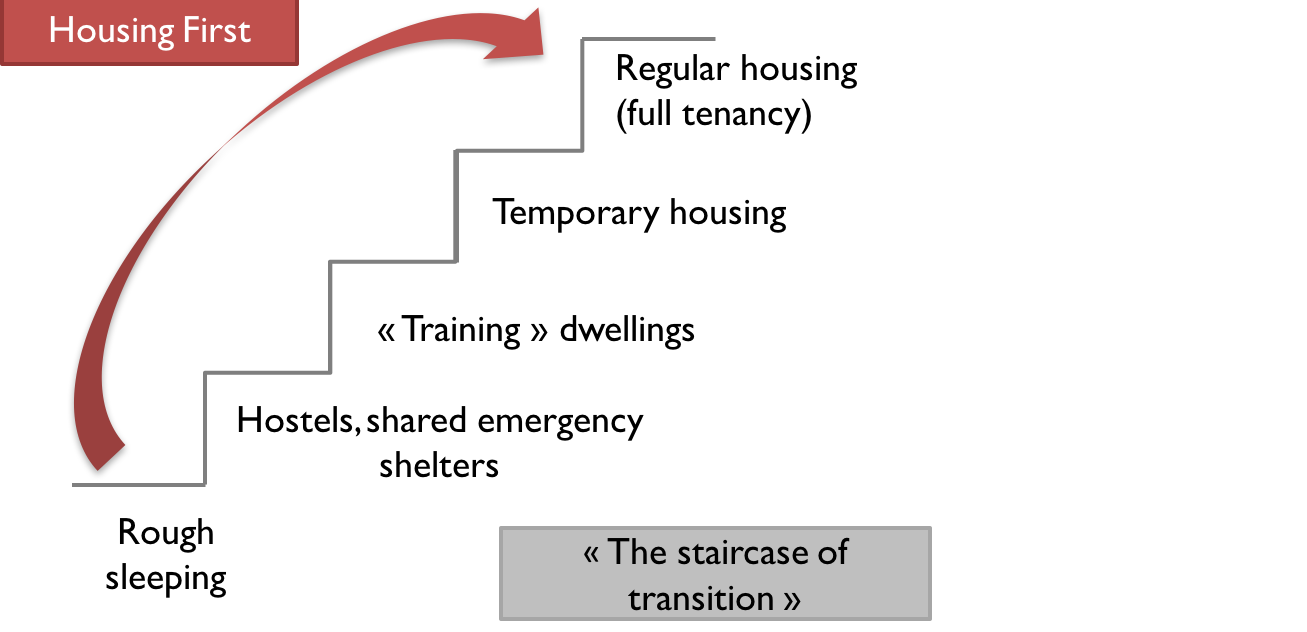

In France, homeless people have to navigate through a complex set of services to make their way to long-term independent housing. The structure of available shelter and housing for the homeless can be compared to a « staircase of transition » (Sahlin, 2005). The steps of the staircase lead gradually from emergency shelters to transitional housing, and finally, to long term independent housing. The main problem is that mobilities along the staircase are nowadays hindered by the scarcity of supply, but also by qualitative inadequacies, which constrain access to a regular, decent home.

What we offer

We promote an alternative approach to the existing staircase system, which is more effective, less expensive, and, more importantly, which better addresses the needs and aspirations of homeless people. This solution is based on the « Housing First » model, which was first initiated in the US. Housing First consists in providing direct access to long-term independent housing, for the chronically homeless undergoing severe mental illnesses and addictions. We would like to generalize the implementation of this model in France, for all the homeless, and not only those with the most complex needs, by providing support to local authorities who wish to make this shift.

Our partners

Read more

We started working on the issue of homelessness in 2015, producing an analysis of the homeless population and the existing accommodation solutions available to them. This analysis was also critical of the current public policies addressing homelessness.

The staircase of transition leading from the streets to an independent home

In France, moving away from the streets to an independent home can be compared to climbing up a staircase built on different steps, ranging from the roughest accommodation solutions (emergency hostels or shelters) to more lasting solutions (supportive housing, settled accomodation). The middle steps correspond to temporary solutions (social reinegration centres, transitional housing, temporary housing).

Within the « staircase of transition » framework, if a formerly homeless person starts climbing-up the steps, it means that less and less support and assistance is required, that the person is more and more « housing ready ». The higher the person climbs, the more privacy and freedom he or she will be awarded and the more ‘normal’ his or her housing solution will become. The ultimate goal driving the staircase model access to a regular rental flat. The logic behind this model is that this goal can only be achieved through a step-by-step integration process.

Moving along the staircase requires social support, enabling progressive empowerment. But it also requires available supply of accomodation at each step of the staircase. Provision of supply depends heavily on funding from the State, which is nowadays confronted to a double problem :

- on the one hand, the demand for homeless accommodation is increasing

- on the other hand, the characteristics of the homeless are changing.

This can be explained by contextual factors, such as migratory flows, but also by structural factors, such as changes in family composition or precarization. Up to now, the State has centred its priorities on emergency shelters and hostels and more settled forms of accommodation.

Mobilities along the staircase are limited

In 2014, 70% of the people evolving through the staircase did not access to long-term, independent housing[1]. The reasons explaining why homeless people are trapped within the system are the following :

1. Qualitative inadequacies of the system

- In spite of important humanisation works, emergency shelters cannot accommodate familes and still operate on a temporary basis : after having been sheltered one or two nights, homeless people are thrown back on the streets. For these people at the bottom of the staircase, making it to the next step is highly unlikely.

- People who made it to the second step, accommodated in social reintegration centres or other forms of transitional housing, are also faced with several difficulties. These centres are selective, they have specific rules (usually they do not allow animals and prohibit alcohol and drug use). But most of all, they impose severe requirements, such as the contractualization of social support and the provision of evidence of integration. These requirements turn out to bes too demanding.

- Finally, the ultimate step of independent long-term housing is impossible to reach : social or private rental flats are too expensive, poorly located, or unsuitable in terms of housing typology. The attribution of social housing units by public authorities and social landlords is highly selective and relies on normative and non-transparent criteria revolving around the alleged « housing readiness » of formerly-homeless potential tenants..

2. Scarcity in accommodation supply for the homeless

- From a quantitative point of view, the staircase model falls short in terms of capacity. There are bottlenecks at each level, which result in longer lengths of stays, small turn-over ratios (except for emergency shelters where these ratios are very high because people are thrown back to the streets).

[1] DREES, INSEE, Action Tank Social and Business analysis

Our offer consists in providing direct and unconditionnal access to long-term indendepent housing for the homeless who are currently trapped in the existing system.

We believe that rapid access to stable housing is a prerequisite for recovery and social inclusion, and that in no way it should be its result.

The Housing First model, a paradigm shift we support

The Housing First (HF) model originated in the United States in a similar « staircase of transition » context to that in France. It consists in providing immediate access to independent, scattered housing for the homeless, on the one hand ; and intensive support to help them sustain such accommodation, on the other hand. Support is provided by pluridisciplinary teams, which come and visit the new tenant on a very frequent basis. In its initial version, the HF approach is both medical and social, and does not target all the homeless population but only a fraction, ie. the most vulnerable, those who are sleeping rough and combine severe mental illnesses and addictions[2].

The evaluations of HF experiments which took place in the past 20 years in North America and European countries show very positive results, be they in terms of sustained accommodation (more than 80%) or in terms of improvement in the quality of life. HF experiments are also legitimized by the cost savings they allow for. They result in important cost savings regarding public sector service use, in terms of homeless accommodation, hospital days, justice spendings… The study on the « At Home/ Chez Soi » HF programme in Canada[3] shows that for heavy users of public services, every $10 invested in HF services resulted in an average savings of $21.72. Cost savings are not systematic though : the study also shows that cost savings are less important (if not null) for people with moderate needs and less intensive use of public services.

Adapting HF to the French context

In France, the diffusion of the HF model is still very limited. In the end of the 2000s, the Goverment tried to prioritize access to long-term independent housing over emergency and temporary accommodation. Unfortunately, the Government failed to deliver. The staircase model is still going strong, and, apart from one initiative called « Un Chez Soi d’Abord », targeting 350 homeless individuals, HF experiments are sparse and loosely coordinated[4].

In March 2017, the Action Tank, in partnership with the Agence nouvelle des solidarités actives (ANSA) published a report called “Housing First : what’s next?”, providing evidence from the French and foreign Housing First experiments and insights on the way the model can be adapted and scaled-up in France.

[2] Housing First : Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives (2016), Oxford University Press, Padgett, B. Henwood, S.Tsemberis. [3] National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report (2014), Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada, Goering, S. Veldhuizen, A. Watson, C. Adair, B. Kopp, E. Latimer, G.Nelson, E. MacNaughton, D.Streiner, T. Aubry. [4] Source Localtis.

Target

Straying from the initial Housing First model, we intend to generalize the Housing First approach to the whole homeless population who is denied access to independent, long-term housing, and not only the homeless population with the most complex needs (50, 000 households). This approach is a “housing led” shift in the way homelessness is dealt with.

Aim

The aim of the project is to provide support to local authorities who wish to shift from a “staircase” model to a “housing led” model, by providing support in the analysis of their existing systems and the design of local action plans.

We identified the following steps for the implementation of the project:

- Analysis of the existing supply in homeless accommodation and social housing on the chosen territory

- Identification of the needs of the targeted cohort

- Resizing of the existing housing and accommodation offer

- Co-construction of a platform for the provision of support with local operators

- Validation of the operational functioning and funding with local operators, local authorities and social landlords

- Change management with the stakeholders involved

- Methodology for the impact assessment

Recent developments

We are currently working with the local authority of Strasbourg, in the East of France, to implement a Housing First – within a broader “housing led” – strategy. The roadmap we are building with a wide range of local stakeholders will serve as an example for the design of a national Housing First strategy.

In short

The challenge

In France, homeless people have to navigate through a complex set of services to make their way to long-term independent housing. The structure of available shelter and housing for the homeless can be compared to a « staircase of transition » (Sahlin, 2005). The steps of the staircase lead gradually from emergency shelters to transitional housing, and finally, to long term independent housing. The main problem is that mobilities along the staircase are nowadays hindered by the scarcity of supply, but also by qualitative inadequacies, which constrain access to a regular, decent home.

What we offer

We promote an alternative approach to the existing staircase system, which is more effective, less expensive, and, more importantly, which better addresses the needs and aspirations of homeless people. This solution is based on the « Housing First » model, which was first initiated in the US. Housing First consists in providing direct access to long-term independent housing, for the chronically homeless undergoing severe mental illnesses and addictions. We would like to generalize the implementation of this model in France, for all the homeless, and not only those with the most complex needs, by providing support to local authorities who wish to make this shift.

Our partners

Read more

We started working on the issue of homelessness in 2015, producing an analysis of the homeless population and the existing accommodation solutions available to them. This analysis was also critical of the current public policies addressing homelessness.

The staircase of transition leading from the streets to an independent home

In France, moving away from the streets to an independent home can be compared to climbing up a staircase built on different steps, ranging from the roughest accommodation solutions (emergency hostels or shelters) to more lasting solutions (supportive housing, settled accomodation). The middle steps correspond to temporary solutions (social reinegration centres, transitional housing, temporary housing).

Within the « staircase of transition » framework, if a formerly homeless person starts climbing-up the steps, it means that less and less support and assistance is required, that the person is more and more « housing ready ». The higher the person climbs, the more privacy and freedom he or she will be awarded and the more ‘normal’ his or her housing solution will become. The ultimate goal driving the staircase model access to a regular rental flat. The logic behind this model is that this goal can only be achieved through a step-by-step integration process.

Moving along the staircase requires social support, enabling progressive empowerment. But it also requires available supply of accomodation at each step of the staircase. Provision of supply depends heavily on funding from the State, which is nowadays confronted to a double problem :

- on the one hand, the demand for homeless accommodation is increasing

- on the other hand, the characteristics of the homeless are changing.

This can be explained by contextual factors, such as migratory flows, but also by structural factors, such as changes in family composition or precarization. Up to now, the State has centred its priorities on emergency shelters and hostels and more settled forms of accommodation.

Mobilities along the staircase are limited

In 2014, 70% of the people evolving through the staircase did not access to long-term, independent housing[1]. The reasons explaining why homeless people are trapped within the system are the following :

1. Qualitative inadequacies of the system

- In spite of important humanisation works, emergency shelters cannot accommodate familes and still operate on a temporary basis : after having been sheltered one or two nights, homeless people are thrown back on the streets. For these people at the bottom of the staircase, making it to the next step is highly unlikely.

- People who made it to the second step, accommodated in social reintegration centres or other forms of transitional housing, are also faced with several difficulties. These centres are selective, they have specific rules (usually they do not allow animals and prohibit alcohol and drug use). But most of all, they impose severe requirements, such as the contractualization of social support and the provision of evidence of integration. These requirements turn out to bes too demanding.

- Finally, the ultimate step of independent long-term housing is impossible to reach : social or private rental flats are too expensive, poorly located, or unsuitable in terms of housing typology. The attribution of social housing units by public authorities and social landlords is highly selective and relies on normative and non-transparent criteria revolving around the alleged « housing readiness » of formerly-homeless potential tenants..

2. Scarcity in accommodation supply for the homeless

- From a quantitative point of view, the staircase model falls short in terms of capacity. There are bottlenecks at each level, which result in longer lengths of stays, small turn-over ratios (except for emergency shelters where these ratios are very high because people are thrown back to the streets).

[1] DREES, INSEE, Action Tank Social and Business analysis

Our offer consists in providing direct and unconditionnal access to long-term indendepent housing for the homeless who are currently trapped in the existing system.

We believe that rapid access to stable housing is a prerequisite for recovery and social inclusion, and that in no way it should be its result.

The Housing First model, a paradigm shift we support

The Housing First (HF) model originated in the United States in a similar « staircase of transition » context to that in France. It consists in providing immediate access to independent, scattered housing for the homeless, on the one hand ; and intensive support to help them sustain such accommodation, on the other hand. Support is provided by pluridisciplinary teams, which come and visit the new tenant on a very frequent basis. In its initial version, the HF approach is both medical and social, and does not target all the homeless population but only a fraction, ie. the most vulnerable, those who are sleeping rough and combine severe mental illnesses and addictions[2].

The evaluations of HF experiments which took place in the past 20 years in North America and European countries show very positive results, be they in terms of sustained accommodation (more than 80%) or in terms of improvement in the quality of life. HF experiments are also legitimized by the cost savings they allow for. They result in important cost savings regarding public sector service use, in terms of homeless accommodation, hospital days, justice spendings… The study on the « At Home/ Chez Soi » HF programme in Canada[3] shows that for heavy users of public services, every $10 invested in HF services resulted in an average savings of $21.72. Cost savings are not systematic though : the study also shows that cost savings are less important (if not null) for people with moderate needs and less intensive use of public services.

Adapting HF to the French context

In France, the diffusion of the HF model is still very limited. In the end of the 2000s, the Goverment tried to prioritize access to long-term independent housing over emergency and temporary accommodation. Unfortunately, the Government failed to deliver. The staircase model is still going strong, and, apart from one initiative called « Un Chez Soi d’Abord », targeting 350 homeless individuals, HF experiments are sparse and loosely coordinated[4].

In March 2017, the Action Tank, in partnership with the Agence nouvelle des solidarités actives (ANSA) published a report called “Housing First : what’s next?”, providing evidence from the French and foreign Housing First experiments and insights on the way the model can be adapted and scaled-up in France.

[2] Housing First : Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives (2016), Oxford University Press, Padgett, B. Henwood, S.Tsemberis. [3] National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report (2014), Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada, Goering, S. Veldhuizen, A. Watson, C. Adair, B. Kopp, E. Latimer, G.Nelson, E. MacNaughton, D.Streiner, T. Aubry. [4] Source Localtis.

Target

Straying from the initial Housing First model, we intend to generalize the Housing First approach to the whole homeless population who is denied access to independent, long-term housing, and not only the homeless population with the most complex needs (50, 000 households). This approach is a “housing led” shift in the way homelessness is dealt with.

Aim

The aim of the project is to provide support to local authorities who wish to shift from a “staircase” model to a “housing led” model, by providing support in the analysis of their existing systems and the design of local action plans.

We identified the following steps for the implementation of the project:

- Analysis of the existing supply in homeless accommodation and social housing on the chosen territory

- Identification of the needs of the targeted cohort

- Resizing of the existing housing and accommodation offer

- Co-construction of a platform for the provision of support with local operators

- Validation of the operational functioning and funding with local operators, local authorities and social landlords

- Change management with the stakeholders involved

- Methodology for the impact assessment

Recent developments

We are currently working with the local authority of Strasbourg, in the East of France, to implement a Housing First – within a broader “housing led” – strategy. The roadmap we are building with a wide range of local stakeholders will serve as an example for the design of a national Housing First strategy.

In short

The challenge

In France, homeless people have to navigate through a complex set of services to make their way to long-term independent housing. The structure of available shelter and housing for the homeless can be compared to a « staircase of transition » (Sahlin, 2005). The steps of the staircase lead gradually from emergency shelters to transitional housing, and finally, to long term independent housing. The main problem is that mobilities along the staircase are nowadays hindered by the scarcity of supply, but also by qualitative inadequacies, which constrain access to a regular, decent home.

What we offer

We promote an alternative approach to the existing staircase system, which is more effective, less expensive, and, more importantly, which better addresses the needs and aspirations of homeless people. This solution is based on the « Housing First » model, which was first initiated in the US. Housing First consists in providing direct access to long-term independent housing, for the chronically homeless undergoing severe mental illnesses and addictions. We would like to generalize the implementation of this model in France, for all the homeless, and not only those with the most complex needs, by providing support to local authorities who wish to make this shift.

Our partners

Read more

We started working on the issue of homelessness in 2015, producing an analysis of the homeless population and the existing accommodation solutions available to them. This analysis was also critical of the current public policies addressing homelessness.

The staircase of transition leading from the streets to an independent home

In France, moving away from the streets to an independent home can be compared to climbing up a staircase built on different steps, ranging from the roughest accommodation solutions (emergency hostels or shelters) to more lasting solutions (supportive housing, settled accomodation). The middle steps correspond to temporary solutions (social reinegration centres, transitional housing, temporary housing).

Within the « staircase of transition » framework, if a formerly homeless person starts climbing-up the steps, it means that less and less support and assistance is required, that the person is more and more « housing ready ». The higher the person climbs, the more privacy and freedom he or she will be awarded and the more ‘normal’ his or her housing solution will become. The ultimate goal driving the staircase model access to a regular rental flat. The logic behind this model is that this goal can only be achieved through a step-by-step integration process.

Moving along the staircase requires social support, enabling progressive empowerment. But it also requires available supply of accomodation at each step of the staircase. Provision of supply depends heavily on funding from the State, which is nowadays confronted to a double problem :

- on the one hand, the demand for homeless accommodation is increasing

- on the other hand, the characteristics of the homeless are changing.

This can be explained by contextual factors, such as migratory flows, but also by structural factors, such as changes in family composition or precarization. Up to now, the State has centred its priorities on emergency shelters and hostels and more settled forms of accommodation.

Mobilities along the staircase are limited

In 2014, 70% of the people evolving through the staircase did not access to long-term, independent housing[1]. The reasons explaining why homeless people are trapped within the system are the following :

1. Qualitative inadequacies of the system

- In spite of important humanisation works, emergency shelters cannot accommodate familes and still operate on a temporary basis : after having been sheltered one or two nights, homeless people are thrown back on the streets. For these people at the bottom of the staircase, making it to the next step is highly unlikely.

- People who made it to the second step, accommodated in social reintegration centres or other forms of transitional housing, are also faced with several difficulties. These centres are selective, they have specific rules (usually they do not allow animals and prohibit alcohol and drug use). But most of all, they impose severe requirements, such as the contractualization of social support and the provision of evidence of integration. These requirements turn out to bes too demanding.

- Finally, the ultimate step of independent long-term housing is impossible to reach : social or private rental flats are too expensive, poorly located, or unsuitable in terms of housing typology. The attribution of social housing units by public authorities and social landlords is highly selective and relies on normative and non-transparent criteria revolving around the alleged « housing readiness » of formerly-homeless potential tenants..

2. Scarcity in accommodation supply for the homeless

- From a quantitative point of view, the staircase model falls short in terms of capacity. There are bottlenecks at each level, which result in longer lengths of stays, small turn-over ratios (except for emergency shelters where these ratios are very high because people are thrown back to the streets).

[1] DREES, INSEE, Action Tank Social and Business analysis

Our offer consists in providing direct and unconditionnal access to long-term indendepent housing for the homeless who are currently trapped in the existing system.

We believe that rapid access to stable housing is a prerequisite for recovery and social inclusion, and that in no way it should be its result.

The Housing First model, a paradigm shift we support

The Housing First (HF) model originated in the United States in a similar « staircase of transition » context to that in France. It consists in providing immediate access to independent, scattered housing for the homeless, on the one hand ; and intensive support to help them sustain such accommodation, on the other hand. Support is provided by pluridisciplinary teams, which come and visit the new tenant on a very frequent basis. In its initial version, the HF approach is both medical and social, and does not target all the homeless population but only a fraction, ie. the most vulnerable, those who are sleeping rough and combine severe mental illnesses and addictions[2].

The evaluations of HF experiments which took place in the past 20 years in North America and European countries show very positive results, be they in terms of sustained accommodation (more than 80%) or in terms of improvement in the quality of life. HF experiments are also legitimized by the cost savings they allow for. They result in important cost savings regarding public sector service use, in terms of homeless accommodation, hospital days, justice spendings… The study on the « At Home/ Chez Soi » HF programme in Canada[3] shows that for heavy users of public services, every $10 invested in HF services resulted in an average savings of $21.72. Cost savings are not systematic though : the study also shows that cost savings are less important (if not null) for people with moderate needs and less intensive use of public services.

Adapting HF to the French context

In France, the diffusion of the HF model is still very limited. In the end of the 2000s, the Goverment tried to prioritize access to long-term independent housing over emergency and temporary accommodation. Unfortunately, the Government failed to deliver. The staircase model is still going strong, and, apart from one initiative called « Un Chez Soi d’Abord », targeting 350 homeless individuals, HF experiments are sparse and loosely coordinated[4].

In March 2017, the Action Tank, in partnership with the Agence nouvelle des solidarités actives (ANSA) published a report called “Housing First : what’s next?”, providing evidence from the French and foreign Housing First experiments and insights on the way the model can be adapted and scaled-up in France.

[2] Housing First : Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives (2016), Oxford University Press, Padgett, B. Henwood, S.Tsemberis. [3] National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report (2014), Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada, Goering, S. Veldhuizen, A. Watson, C. Adair, B. Kopp, E. Latimer, G.Nelson, E. MacNaughton, D.Streiner, T. Aubry. [4] Source Localtis.

Target

Straying from the initial Housing First model, we intend to generalize the Housing First approach to the whole homeless population who is denied access to independent, long-term housing, and not only the homeless population with the most complex needs (50, 000 households). This approach is a “housing led” shift in the way homelessness is dealt with.

Aim

The aim of the project is to provide support to local authorities who wish to shift from a “staircase” model to a “housing led” model, by providing support in the analysis of their existing systems and the design of local action plans.

We identified the following steps for the implementation of the project:

- Analysis of the existing supply in homeless accommodation and social housing on the chosen territory

- Identification of the needs of the targeted cohort

- Resizing of the existing housing and accommodation offer

- Co-construction of a platform for the provision of support with local operators

- Validation of the operational functioning and funding with local operators, local authorities and social landlords

- Change management with the stakeholders involved

- Methodology for the impact assessment

Recent developments

We are currently working with the local authority of Strasbourg, in the East of France, to implement a Housing First – within a broader “housing led” – strategy. The roadmap we are building with a wide range of local stakeholders will serve as an example for the design of a national Housing First strategy.

In short

The challenge

In France, homeless people have to navigate through a complex set of services to make their way to long-term independent housing. The structure of available shelter and housing for the homeless can be compared to a « staircase of transition » (Sahlin, 2005). The steps of the staircase lead gradually from emergency shelters to transitional housing, and finally, to long term independent housing. The main problem is that mobilities along the staircase are nowadays hindered by the scarcity of supply, but also by qualitative inadequacies, which constrain access to a regular, decent home.

What we offer

We promote an alternative approach to the existing staircase system, which is more effective, less expensive, and, more importantly, which better addresses the needs and aspirations of homeless people. This solution is based on the « Housing First » model, which was first initiated in the US. Housing First consists in providing direct access to long-term independent housing, for the chronically homeless undergoing severe mental illnesses and addictions. We would like to generalize the implementation of this model in France, for all the homeless, and not only those with the most complex needs, by providing support to local authorities who wish to make this shift.

Our partners

Read more

We started working on the issue of homelessness in 2015, producing an analysis of the homeless population and the existing accommodation solutions available to them. This analysis was also critical of the current public policies addressing homelessness.

The staircase of transition leading from the streets to an independent home

In France, moving away from the streets to an independent home can be compared to climbing up a staircase built on different steps, ranging from the roughest accommodation solutions (emergency hostels or shelters) to more lasting solutions (supportive housing, settled accomodation). The middle steps correspond to temporary solutions (social reinegration centres, transitional housing, temporary housing).

Within the « staircase of transition » framework, if a formerly homeless person starts climbing-up the steps, it means that less and less support and assistance is required, that the person is more and more « housing ready ». The higher the person climbs, the more privacy and freedom he or she will be awarded and the more ‘normal’ his or her housing solution will become. The ultimate goal driving the staircase model access to a regular rental flat. The logic behind this model is that this goal can only be achieved through a step-by-step integration process.

Moving along the staircase requires social support, enabling progressive empowerment. But it also requires available supply of accomodation at each step of the staircase. Provision of supply depends heavily on funding from the State, which is nowadays confronted to a double problem :

- on the one hand, the demand for homeless accommodation is increasing

- on the other hand, the characteristics of the homeless are changing.

This can be explained by contextual factors, such as migratory flows, but also by structural factors, such as changes in family composition or precarization. Up to now, the State has centred its priorities on emergency shelters and hostels and more settled forms of accommodation.

Mobilities along the staircase are limited

In 2014, 70% of the people evolving through the staircase did not access to long-term, independent housing[1]. The reasons explaining why homeless people are trapped within the system are the following :

1. Qualitative inadequacies of the system

- In spite of important humanisation works, emergency shelters cannot accommodate familes and still operate on a temporary basis : after having been sheltered one or two nights, homeless people are thrown back on the streets. For these people at the bottom of the staircase, making it to the next step is highly unlikely.

- People who made it to the second step, accommodated in social reintegration centres or other forms of transitional housing, are also faced with several difficulties. These centres are selective, they have specific rules (usually they do not allow animals and prohibit alcohol and drug use). But most of all, they impose severe requirements, such as the contractualization of social support and the provision of evidence of integration. These requirements turn out to bes too demanding.

- Finally, the ultimate step of independent long-term housing is impossible to reach : social or private rental flats are too expensive, poorly located, or unsuitable in terms of housing typology. The attribution of social housing units by public authorities and social landlords is highly selective and relies on normative and non-transparent criteria revolving around the alleged « housing readiness » of formerly-homeless potential tenants..

2. Scarcity in accommodation supply for the homeless

- From a quantitative point of view, the staircase model falls short in terms of capacity. There are bottlenecks at each level, which result in longer lengths of stays, small turn-over ratios (except for emergency shelters where these ratios are very high because people are thrown back to the streets).

[1] DREES, INSEE, Action Tank Social and Business analysis

Our offer consists in providing direct and unconditionnal access to long-term indendepent housing for the homeless who are currently trapped in the existing system.

We believe that rapid access to stable housing is a prerequisite for recovery and social inclusion, and that in no way it should be its result.

The Housing First model, a paradigm shift we support

The Housing First (HF) model originated in the United States in a similar « staircase of transition » context to that in France. It consists in providing immediate access to independent, scattered housing for the homeless, on the one hand ; and intensive support to help them sustain such accommodation, on the other hand. Support is provided by pluridisciplinary teams, which come and visit the new tenant on a very frequent basis. In its initial version, the HF approach is both medical and social, and does not target all the homeless population but only a fraction, ie. the most vulnerable, those who are sleeping rough and combine severe mental illnesses and addictions[2].

The evaluations of HF experiments which took place in the past 20 years in North America and European countries show very positive results, be they in terms of sustained accommodation (more than 80%) or in terms of improvement in the quality of life. HF experiments are also legitimized by the cost savings they allow for. They result in important cost savings regarding public sector service use, in terms of homeless accommodation, hospital days, justice spendings… The study on the « At Home/ Chez Soi » HF programme in Canada[3] shows that for heavy users of public services, every $10 invested in HF services resulted in an average savings of $21.72. Cost savings are not systematic though : the study also shows that cost savings are less important (if not null) for people with moderate needs and less intensive use of public services.

Adapting HF to the French context

In France, the diffusion of the HF model is still very limited. In the end of the 2000s, the Goverment tried to prioritize access to long-term independent housing over emergency and temporary accommodation. Unfortunately, the Government failed to deliver. The staircase model is still going strong, and, apart from one initiative called « Un Chez Soi d’Abord », targeting 350 homeless individuals, HF experiments are sparse and loosely coordinated[4].

In March 2017, the Action Tank, in partnership with the Agence nouvelle des solidarités actives (ANSA) published a report called “Housing First : what’s next?”, providing evidence from the French and foreign Housing First experiments and insights on the way the model can be adapted and scaled-up in France.

[2] Housing First : Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives (2016), Oxford University Press, Padgett, B. Henwood, S.Tsemberis. [3] National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report (2014), Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada, Goering, S. Veldhuizen, A. Watson, C. Adair, B. Kopp, E. Latimer, G.Nelson, E. MacNaughton, D.Streiner, T. Aubry. [4] Source Localtis.

Target

Straying from the initial Housing First model, we intend to generalize the Housing First approach to the whole homeless population who is denied access to independent, long-term housing, and not only the homeless population with the most complex needs (50, 000 households). This approach is a “housing led” shift in the way homelessness is dealt with.

Aim

The aim of the project is to provide support to local authorities who wish to shift from a “staircase” model to a “housing led” model, by providing support in the analysis of their existing systems and the design of local action plans.

We identified the following steps for the implementation of the project:

- Analysis of the existing supply in homeless accommodation and social housing on the chosen territory

- Identification of the needs of the targeted cohort

- Resizing of the existing housing and accommodation offer

- Co-construction of a platform for the provision of support with local operators

- Validation of the operational functioning and funding with local operators, local authorities and social landlords

- Change management with the stakeholders involved

- Methodology for the impact assessment

Recent developments

We are currently working with the local authority of Strasbourg, in the East of France, to implement a Housing First – within a broader “housing led” – strategy. The roadmap we are building with a wide range of local stakeholders will serve as an example for the design of a national Housing First strategy.

In short

The challenge

In France, homeless people have to navigate through a complex set of services to make their way to long-term independent housing. The structure of available shelter and housing for the homeless can be compared to a « staircase of transition » (Sahlin, 2005). The steps of the staircase lead gradually from emergency shelters to transitional housing, and finally, to long term independent housing. The main problem is that mobilities along the staircase are nowadays hindered by the scarcity of supply, but also by qualitative inadequacies, which constrain access to a regular, decent home.

What we offer

We promote an alternative approach to the existing staircase system, which is more effective, less expensive, and, more importantly, which better addresses the needs and aspirations of homeless people. This solution is based on the « Housing First » model, which was first initiated in the US. Housing First consists in providing direct access to long-term independent housing, for the chronically homeless undergoing severe mental illnesses and addictions. We would like to generalize the implementation of this model in France, for all the homeless, and not only those with the most complex needs, by providing support to local authorities who wish to make this shift.

Our partners

Read more

We started working on the issue of homelessness in 2015, producing an analysis of the homeless population and the existing accommodation solutions available to them. This analysis was also critical of the current public policies addressing homelessness.

The staircase of transition leading from the streets to an independent home

In France, moving away from the streets to an independent home can be compared to climbing up a staircase built on different steps, ranging from the roughest accommodation solutions (emergency hostels or shelters) to more lasting solutions (supportive housing, settled accomodation). The middle steps correspond to temporary solutions (social reinegration centres, transitional housing, temporary housing).

Within the « staircase of transition » framework, if a formerly homeless person starts climbing-up the steps, it means that less and less support and assistance is required, that the person is more and more « housing ready ». The higher the person climbs, the more privacy and freedom he or she will be awarded and the more ‘normal’ his or her housing solution will become. The ultimate goal driving the staircase model access to a regular rental flat. The logic behind this model is that this goal can only be achieved through a step-by-step integration process.

Moving along the staircase requires social support, enabling progressive empowerment. But it also requires available supply of accomodation at each step of the staircase. Provision of supply depends heavily on funding from the State, which is nowadays confronted to a double problem :

- on the one hand, the demand for homeless accommodation is increasing

- on the other hand, the characteristics of the homeless are changing.

This can be explained by contextual factors, such as migratory flows, but also by structural factors, such as changes in family composition or precarization. Up to now, the State has centred its priorities on emergency shelters and hostels and more settled forms of accommodation.

Mobilities along the staircase are limited

In 2014, 70% of the people evolving through the staircase did not access to long-term, independent housing[1]. The reasons explaining why homeless people are trapped within the system are the following :

1. Qualitative inadequacies of the system

- In spite of important humanisation works, emergency shelters cannot accommodate familes and still operate on a temporary basis : after having been sheltered one or two nights, homeless people are thrown back on the streets. For these people at the bottom of the staircase, making it to the next step is highly unlikely.

- People who made it to the second step, accommodated in social reintegration centres or other forms of transitional housing, are also faced with several difficulties. These centres are selective, they have specific rules (usually they do not allow animals and prohibit alcohol and drug use). But most of all, they impose severe requirements, such as the contractualization of social support and the provision of evidence of integration. These requirements turn out to bes too demanding.

- Finally, the ultimate step of independent long-term housing is impossible to reach : social or private rental flats are too expensive, poorly located, or unsuitable in terms of housing typology. The attribution of social housing units by public authorities and social landlords is highly selective and relies on normative and non-transparent criteria revolving around the alleged « housing readiness » of formerly-homeless potential tenants..

2. Scarcity in accommodation supply for the homeless

- From a quantitative point of view, the staircase model falls short in terms of capacity. There are bottlenecks at each level, which result in longer lengths of stays, small turn-over ratios (except for emergency shelters where these ratios are very high because people are thrown back to the streets).

[1] DREES, INSEE, Action Tank Social and Business analysis

Our offer consists in providing direct and unconditionnal access to long-term indendepent housing for the homeless who are currently trapped in the existing system.

We believe that rapid access to stable housing is a prerequisite for recovery and social inclusion, and that in no way it should be its result.

The Housing First model, a paradigm shift we support

The Housing First (HF) model originated in the United States in a similar « staircase of transition » context to that in France. It consists in providing immediate access to independent, scattered housing for the homeless, on the one hand ; and intensive support to help them sustain such accommodation, on the other hand. Support is provided by pluridisciplinary teams, which come and visit the new tenant on a very frequent basis. In its initial version, the HF approach is both medical and social, and does not target all the homeless population but only a fraction, ie. the most vulnerable, those who are sleeping rough and combine severe mental illnesses and addictions[2].

The evaluations of HF experiments which took place in the past 20 years in North America and European countries show very positive results, be they in terms of sustained accommodation (more than 80%) or in terms of improvement in the quality of life. HF experiments are also legitimized by the cost savings they allow for. They result in important cost savings regarding public sector service use, in terms of homeless accommodation, hospital days, justice spendings… The study on the « At Home/ Chez Soi » HF programme in Canada[3] shows that for heavy users of public services, every $10 invested in HF services resulted in an average savings of $21.72. Cost savings are not systematic though : the study also shows that cost savings are less important (if not null) for people with moderate needs and less intensive use of public services.

Adapting HF to the French context

In France, the diffusion of the HF model is still very limited. In the end of the 2000s, the Goverment tried to prioritize access to long-term independent housing over emergency and temporary accommodation. Unfortunately, the Government failed to deliver. The staircase model is still going strong, and, apart from one initiative called « Un Chez Soi d’Abord », targeting 350 homeless individuals, HF experiments are sparse and loosely coordinated[4].

In March 2017, the Action Tank, in partnership with the Agence nouvelle des solidarités actives (ANSA) published a report called “Housing First : what’s next?”, providing evidence from the French and foreign Housing First experiments and insights on the way the model can be adapted and scaled-up in France.

[2] Housing First : Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives (2016), Oxford University Press, Padgett, B. Henwood, S.Tsemberis. [3] National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report (2014), Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada, Goering, S. Veldhuizen, A. Watson, C. Adair, B. Kopp, E. Latimer, G.Nelson, E. MacNaughton, D.Streiner, T. Aubry. [4] Source Localtis.

Target

Straying from the initial Housing First model, we intend to generalize the Housing First approach to the whole homeless population who is denied access to independent, long-term housing, and not only the homeless population with the most complex needs (50, 000 households). This approach is a “housing led” shift in the way homelessness is dealt with.

Aim

The aim of the project is to provide support to local authorities who wish to shift from a “staircase” model to a “housing led” model, by providing support in the analysis of their existing systems and the design of local action plans.

We identified the following steps for the implementation of the project:

- Analysis of the existing supply in homeless accommodation and social housing on the chosen territory

- Identification of the needs of the targeted cohort

- Resizing of the existing housing and accommodation offer

- Co-construction of a platform for the provision of support with local operators

- Validation of the operational functioning and funding with local operators, local authorities and social landlords

- Change management with the stakeholders involved

- Methodology for the impact assessment

Recent developments

We are currently working with the local authority of Strasbourg, in the East of France, to implement a Housing First – within a broader “housing led” – strategy. The roadmap we are building with a wide range of local stakeholders will serve as an example for the design of a national Housing First strategy.

In short

The challenge

In France, homeless people have to navigate through a complex set of services to make their way to long-term independent housing. The structure of available shelter and housing for the homeless can be compared to a « staircase of transition » (Sahlin, 2005). The steps of the staircase lead gradually from emergency shelters to transitional housing, and finally, to long term independent housing. The main problem is that mobilities along the staircase are nowadays hindered by the scarcity of supply, but also by qualitative inadequacies, which constrain access to a regular, decent home.

What we offer

We promote an alternative approach to the existing staircase system, which is more effective, less expensive, and, more importantly, which better addresses the needs and aspirations of homeless people. This solution is based on the « Housing First » model, which was first initiated in the US. Housing First consists in providing direct access to long-term independent housing, for the chronically homeless undergoing severe mental illnesses and addictions. We would like to generalize the implementation of this model in France, for all the homeless, and not only those with the most complex needs, by providing support to local authorities who wish to make this shift.

Our partners

Read more

We started working on the issue of homelessness in 2015, producing an analysis of the homeless population and the existing accommodation solutions available to them. This analysis was also critical of the current public policies addressing homelessness.

The staircase of transition leading from the streets to an independent home

In France, moving away from the streets to an independent home can be compared to climbing up a staircase built on different steps, ranging from the roughest accommodation solutions (emergency hostels or shelters) to more lasting solutions (supportive housing, settled accomodation). The middle steps correspond to temporary solutions (social reinegration centres, transitional housing, temporary housing).

Within the « staircase of transition » framework, if a formerly homeless person starts climbing-up the steps, it means that less and less support and assistance is required, that the person is more and more « housing ready ». The higher the person climbs, the more privacy and freedom he or she will be awarded and the more ‘normal’ his or her housing solution will become. The ultimate goal driving the staircase model access to a regular rental flat. The logic behind this model is that this goal can only be achieved through a step-by-step integration process.

Moving along the staircase requires social support, enabling progressive empowerment. But it also requires available supply of accomodation at each step of the staircase. Provision of supply depends heavily on funding from the State, which is nowadays confronted to a double problem :

- on the one hand, the demand for homeless accommodation is increasing

- on the other hand, the characteristics of the homeless are changing.

This can be explained by contextual factors, such as migratory flows, but also by structural factors, such as changes in family composition or precarization. Up to now, the State has centred its priorities on emergency shelters and hostels and more settled forms of accommodation.

Mobilities along the staircase are limited

In 2014, 70% of the people evolving through the staircase did not access to long-term, independent housing[1]. The reasons explaining why homeless people are trapped within the system are the following :

1. Qualitative inadequacies of the system

- In spite of important humanisation works, emergency shelters cannot accommodate familes and still operate on a temporary basis : after having been sheltered one or two nights, homeless people are thrown back on the streets. For these people at the bottom of the staircase, making it to the next step is highly unlikely.

- People who made it to the second step, accommodated in social reintegration centres or other forms of transitional housing, are also faced with several difficulties. These centres are selective, they have specific rules (usually they do not allow animals and prohibit alcohol and drug use). But most of all, they impose severe requirements, such as the contractualization of social support and the provision of evidence of integration. These requirements turn out to bes too demanding.

- Finally, the ultimate step of independent long-term housing is impossible to reach : social or private rental flats are too expensive, poorly located, or unsuitable in terms of housing typology. The attribution of social housing units by public authorities and social landlords is highly selective and relies on normative and non-transparent criteria revolving around the alleged « housing readiness » of formerly-homeless potential tenants..

2. Scarcity in accommodation supply for the homeless

- From a quantitative point of view, the staircase model falls short in terms of capacity. There are bottlenecks at each level, which result in longer lengths of stays, small turn-over ratios (except for emergency shelters where these ratios are very high because people are thrown back to the streets).

[1] DREES, INSEE, Action Tank Social and Business analysis

Our offer consists in providing direct and unconditionnal access to long-term indendepent housing for the homeless who are currently trapped in the existing system.

We believe that rapid access to stable housing is a prerequisite for recovery and social inclusion, and that in no way it should be its result.

The Housing First model, a paradigm shift we support

The Housing First (HF) model originated in the United States in a similar « staircase of transition » context to that in France. It consists in providing immediate access to independent, scattered housing for the homeless, on the one hand ; and intensive support to help them sustain such accommodation, on the other hand. Support is provided by pluridisciplinary teams, which come and visit the new tenant on a very frequent basis. In its initial version, the HF approach is both medical and social, and does not target all the homeless population but only a fraction, ie. the most vulnerable, those who are sleeping rough and combine severe mental illnesses and addictions[2].

The evaluations of HF experiments which took place in the past 20 years in North America and European countries show very positive results, be they in terms of sustained accommodation (more than 80%) or in terms of improvement in the quality of life. HF experiments are also legitimized by the cost savings they allow for. They result in important cost savings regarding public sector service use, in terms of homeless accommodation, hospital days, justice spendings… The study on the « At Home/ Chez Soi » HF programme in Canada[3] shows that for heavy users of public services, every $10 invested in HF services resulted in an average savings of $21.72. Cost savings are not systematic though : the study also shows that cost savings are less important (if not null) for people with moderate needs and less intensive use of public services.

Adapting HF to the French context

In France, the diffusion of the HF model is still very limited. In the end of the 2000s, the Goverment tried to prioritize access to long-term independent housing over emergency and temporary accommodation. Unfortunately, the Government failed to deliver. The staircase model is still going strong, and, apart from one initiative called « Un Chez Soi d’Abord », targeting 350 homeless individuals, HF experiments are sparse and loosely coordinated[4].

In March 2017, the Action Tank, in partnership with the Agence nouvelle des solidarités actives (ANSA) published a report called “Housing First : what’s next?”, providing evidence from the French and foreign Housing First experiments and insights on the way the model can be adapted and scaled-up in France.

[2] Housing First : Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives (2016), Oxford University Press, Padgett, B. Henwood, S.Tsemberis. [3] National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report (2014), Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada, Goering, S. Veldhuizen, A. Watson, C. Adair, B. Kopp, E. Latimer, G.Nelson, E. MacNaughton, D.Streiner, T. Aubry. [4] Source Localtis.

Target

Straying from the initial Housing First model, we intend to generalize the Housing First approach to the whole homeless population who is denied access to independent, long-term housing, and not only the homeless population with the most complex needs (50, 000 households). This approach is a “housing led” shift in the way homelessness is dealt with.

Aim

The aim of the project is to provide support to local authorities who wish to shift from a “staircase” model to a “housing led” model, by providing support in the analysis of their existing systems and the design of local action plans.

We identified the following steps for the implementation of the project:

- Analysis of the existing supply in homeless accommodation and social housing on the chosen territory

- Identification of the needs of the targeted cohort

- Resizing of the existing housing and accommodation offer

- Co-construction of a platform for the provision of support with local operators

- Validation of the operational functioning and funding with local operators, local authorities and social landlords

- Change management with the stakeholders involved

- Methodology for the impact assessment

Recent developments

We are currently working with the local authority of Strasbourg, in the East of France, to implement a Housing First – within a broader “housing led” – strategy. The roadmap we are building with a wide range of local stakeholders will serve as an example for the design of a national Housing First strategy.

In short

The challenge

In France, homeless people have to navigate through a complex set of services to make their way to long-term independent housing. The structure of available shelter and housing for the homeless can be compared to a « staircase of transition » (Sahlin, 2005). The steps of the staircase lead gradually from emergency shelters to transitional housing, and finally, to long term independent housing. The main problem is that mobilities along the staircase are nowadays hindered by the scarcity of supply, but also by qualitative inadequacies, which constrain access to a regular, decent home.

What we offer

We promote an alternative approach to the existing staircase system, which is more effective, less expensive, and, more importantly, which better addresses the needs and aspirations of homeless people. This solution is based on the « Housing First » model, which was first initiated in the US. Housing First consists in providing direct access to long-term independent housing, for the chronically homeless undergoing severe mental illnesses and addictions. We would like to generalize the implementation of this model in France, for all the homeless, and not only those with the most complex needs, by providing support to local authorities who wish to make this shift.

Our partners

Read more

We started working on the issue of homelessness in 2015, producing an analysis of the homeless population and the existing accommodation solutions available to them. This analysis was also critical of the current public policies addressing homelessness.

The staircase of transition leading from the streets to an independent home

In France, moving away from the streets to an independent home can be compared to climbing up a staircase built on different steps, ranging from the roughest accommodation solutions (emergency hostels or shelters) to more lasting solutions (supportive housing, settled accomodation). The middle steps correspond to temporary solutions (social reinegration centres, transitional housing, temporary housing).

Within the « staircase of transition » framework, if a formerly homeless person starts climbing-up the steps, it means that less and less support and assistance is required, that the person is more and more « housing ready ». The higher the person climbs, the more privacy and freedom he or she will be awarded and the more ‘normal’ his or her housing solution will become. The ultimate goal driving the staircase model access to a regular rental flat. The logic behind this model is that this goal can only be achieved through a step-by-step integration process.

Moving along the staircase requires social support, enabling progressive empowerment. But it also requires available supply of accomodation at each step of the staircase. Provision of supply depends heavily on funding from the State, which is nowadays confronted to a double problem :

- on the one hand, the demand for homeless accommodation is increasing

- on the other hand, the characteristics of the homeless are changing.

This can be explained by contextual factors, such as migratory flows, but also by structural factors, such as changes in family composition or precarization. Up to now, the State has centred its priorities on emergency shelters and hostels and more settled forms of accommodation.

Mobilities along the staircase are limited

In 2014, 70% of the people evolving through the staircase did not access to long-term, independent housing[1]. The reasons explaining why homeless people are trapped within the system are the following :

1. Qualitative inadequacies of the system

- In spite of important humanisation works, emergency shelters cannot accommodate familes and still operate on a temporary basis : after having been sheltered one or two nights, homeless people are thrown back on the streets. For these people at the bottom of the staircase, making it to the next step is highly unlikely.

- People who made it to the second step, accommodated in social reintegration centres or other forms of transitional housing, are also faced with several difficulties. These centres are selective, they have specific rules (usually they do not allow animals and prohibit alcohol and drug use). But most of all, they impose severe requirements, such as the contractualization of social support and the provision of evidence of integration. These requirements turn out to bes too demanding.

- Finally, the ultimate step of independent long-term housing is impossible to reach : social or private rental flats are too expensive, poorly located, or unsuitable in terms of housing typology. The attribution of social housing units by public authorities and social landlords is highly selective and relies on normative and non-transparent criteria revolving around the alleged « housing readiness » of formerly-homeless potential tenants..

2. Scarcity in accommodation supply for the homeless

- From a quantitative point of view, the staircase model falls short in terms of capacity. There are bottlenecks at each level, which result in longer lengths of stays, small turn-over ratios (except for emergency shelters where these ratios are very high because people are thrown back to the streets).

[1] DREES, INSEE, Action Tank Social and Business analysis

Our offer consists in providing direct and unconditionnal access to long-term indendepent housing for the homeless who are currently trapped in the existing system.

We believe that rapid access to stable housing is a prerequisite for recovery and social inclusion, and that in no way it should be its result.

The Housing First model, a paradigm shift we support

The Housing First (HF) model originated in the United States in a similar « staircase of transition » context to that in France. It consists in providing immediate access to independent, scattered housing for the homeless, on the one hand ; and intensive support to help them sustain such accommodation, on the other hand. Support is provided by pluridisciplinary teams, which come and visit the new tenant on a very frequent basis. In its initial version, the HF approach is both medical and social, and does not target all the homeless population but only a fraction, ie. the most vulnerable, those who are sleeping rough and combine severe mental illnesses and addictions[2].

The evaluations of HF experiments which took place in the past 20 years in North America and European countries show very positive results, be they in terms of sustained accommodation (more than 80%) or in terms of improvement in the quality of life. HF experiments are also legitimized by the cost savings they allow for. They result in important cost savings regarding public sector service use, in terms of homeless accommodation, hospital days, justice spendings… The study on the « At Home/ Chez Soi » HF programme in Canada[3] shows that for heavy users of public services, every $10 invested in HF services resulted in an average savings of $21.72. Cost savings are not systematic though : the study also shows that cost savings are less important (if not null) for people with moderate needs and less intensive use of public services.

Adapting HF to the French context

In France, the diffusion of the HF model is still very limited. In the end of the 2000s, the Goverment tried to prioritize access to long-term independent housing over emergency and temporary accommodation. Unfortunately, the Government failed to deliver. The staircase model is still going strong, and, apart from one initiative called « Un Chez Soi d’Abord », targeting 350 homeless individuals, HF experiments are sparse and loosely coordinated[4].

In March 2017, the Action Tank, in partnership with the Agence nouvelle des solidarités actives (ANSA) published a report called “Housing First : what’s next?”, providing evidence from the French and foreign Housing First experiments and insights on the way the model can be adapted and scaled-up in France.

[2] Housing First : Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives (2016), Oxford University Press, Padgett, B. Henwood, S.Tsemberis. [3] National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report (2014), Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada, Goering, S. Veldhuizen, A. Watson, C. Adair, B. Kopp, E. Latimer, G.Nelson, E. MacNaughton, D.Streiner, T. Aubry. [4] Source Localtis.

Target

Straying from the initial Housing First model, we intend to generalize the Housing First approach to the whole homeless population who is denied access to independent, long-term housing, and not only the homeless population with the most complex needs (50, 000 households). This approach is a “housing led” shift in the way homelessness is dealt with.

Aim

The aim of the project is to provide support to local authorities who wish to shift from a “staircase” model to a “housing led” model, by providing support in the analysis of their existing systems and the design of local action plans.

We identified the following steps for the implementation of the project:

- Analysis of the existing supply in homeless accommodation and social housing on the chosen territory

- Identification of the needs of the targeted cohort

- Resizing of the existing housing and accommodation offer

- Co-construction of a platform for the provision of support with local operators

- Validation of the operational functioning and funding with local operators, local authorities and social landlords

- Change management with the stakeholders involved

- Methodology for the impact assessment

Recent developments

We are currently working with the local authority of Strasbourg, in the East of France, to implement a Housing First – within a broader “housing led” – strategy. The roadmap we are building with a wide range of local stakeholders will serve as an example for the design of a national Housing First strategy.

In short

The challenge

In France, homeless people have to navigate through a complex set of services to make their way to long-term independent housing. The structure of available shelter and housing for the homeless can be compared to a « staircase of transition » (Sahlin, 2005). The steps of the staircase lead gradually from emergency shelters to transitional housing, and finally, to long term independent housing. The main problem is that mobilities along the staircase are nowadays hindered by the scarcity of supply, but also by qualitative inadequacies, which constrain access to a regular, decent home.

What we offer

We promote an alternative approach to the existing staircase system, which is more effective, less expensive, and, more importantly, which better addresses the needs and aspirations of homeless people. This solution is based on the « Housing First » model, which was first initiated in the US. Housing First consists in providing direct access to long-term independent housing, for the chronically homeless undergoing severe mental illnesses and addictions. We would like to generalize the implementation of this model in France, for all the homeless, and not only those with the most complex needs, by providing support to local authorities who wish to make this shift.

Our partners

Read more

We started working on the issue of homelessness in 2015, producing an analysis of the homeless population and the existing accommodation solutions available to them. This analysis was also critical of the current public policies addressing homelessness.

The staircase of transition leading from the streets to an independent home

In France, moving away from the streets to an independent home can be compared to climbing up a staircase built on different steps, ranging from the roughest accommodation solutions (emergency hostels or shelters) to more lasting solutions (supportive housing, settled accomodation). The middle steps correspond to temporary solutions (social reinegration centres, transitional housing, temporary housing).

Within the « staircase of transition » framework, if a formerly homeless person starts climbing-up the steps, it means that less and less support and assistance is required, that the person is more and more « housing ready ». The higher the person climbs, the more privacy and freedom he or she will be awarded and the more ‘normal’ his or her housing solution will become. The ultimate goal driving the staircase model access to a regular rental flat. The logic behind this model is that this goal can only be achieved through a step-by-step integration process.

Moving along the staircase requires social support, enabling progressive empowerment. But it also requires available supply of accomodation at each step of the staircase. Provision of supply depends heavily on funding from the State, which is nowadays confronted to a double problem :

- on the one hand, the demand for homeless accommodation is increasing

- on the other hand, the characteristics of the homeless are changing.

This can be explained by contextual factors, such as migratory flows, but also by structural factors, such as changes in family composition or precarization. Up to now, the State has centred its priorities on emergency shelters and hostels and more settled forms of accommodation.

Mobilities along the staircase are limited

In 2014, 70% of the people evolving through the staircase did not access to long-term, independent housing[1]. The reasons explaining why homeless people are trapped within the system are the following :

1. Qualitative inadequacies of the system

- In spite of important humanisation works, emergency shelters cannot accommodate familes and still operate on a temporary basis : after having been sheltered one or two nights, homeless people are thrown back on the streets. For these people at the bottom of the staircase, making it to the next step is highly unlikely.

- People who made it to the second step, accommodated in social reintegration centres or other forms of transitional housing, are also faced with several difficulties. These centres are selective, they have specific rules (usually they do not allow animals and prohibit alcohol and drug use). But most of all, they impose severe requirements, such as the contractualization of social support and the provision of evidence of integration. These requirements turn out to bes too demanding.

- Finally, the ultimate step of independent long-term housing is impossible to reach : social or private rental flats are too expensive, poorly located, or unsuitable in terms of housing typology. The attribution of social housing units by public authorities and social landlords is highly selective and relies on normative and non-transparent criteria revolving around the alleged « housing readiness » of formerly-homeless potential tenants..

2. Scarcity in accommodation supply for the homeless

- From a quantitative point of view, the staircase model falls short in terms of capacity. There are bottlenecks at each level, which result in longer lengths of stays, small turn-over ratios (except for emergency shelters where these ratios are very high because people are thrown back to the streets).

[1] DREES, INSEE, Action Tank Social and Business analysis

Our offer consists in providing direct and unconditionnal access to long-term indendepent housing for the homeless who are currently trapped in the existing system.

We believe that rapid access to stable housing is a prerequisite for recovery and social inclusion, and that in no way it should be its result.

The Housing First model, a paradigm shift we support

The Housing First (HF) model originated in the United States in a similar « staircase of transition » context to that in France. It consists in providing immediate access to independent, scattered housing for the homeless, on the one hand ; and intensive support to help them sustain such accommodation, on the other hand. Support is provided by pluridisciplinary teams, which come and visit the new tenant on a very frequent basis. In its initial version, the HF approach is both medical and social, and does not target all the homeless population but only a fraction, ie. the most vulnerable, those who are sleeping rough and combine severe mental illnesses and addictions[2].

The evaluations of HF experiments which took place in the past 20 years in North America and European countries show very positive results, be they in terms of sustained accommodation (more than 80%) or in terms of improvement in the quality of life. HF experiments are also legitimized by the cost savings they allow for. They result in important cost savings regarding public sector service use, in terms of homeless accommodation, hospital days, justice spendings… The study on the « At Home/ Chez Soi » HF programme in Canada[3] shows that for heavy users of public services, every $10 invested in HF services resulted in an average savings of $21.72. Cost savings are not systematic though : the study also shows that cost savings are less important (if not null) for people with moderate needs and less intensive use of public services.

Adapting HF to the French context

In France, the diffusion of the HF model is still very limited. In the end of the 2000s, the Goverment tried to prioritize access to long-term independent housing over emergency and temporary accommodation. Unfortunately, the Government failed to deliver. The staircase model is still going strong, and, apart from one initiative called « Un Chez Soi d’Abord », targeting 350 homeless individuals, HF experiments are sparse and loosely coordinated[4].

In March 2017, the Action Tank, in partnership with the Agence nouvelle des solidarités actives (ANSA) published a report called “Housing First : what’s next?”, providing evidence from the French and foreign Housing First experiments and insights on the way the model can be adapted and scaled-up in France.

[2] Housing First : Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives (2016), Oxford University Press, Padgett, B. Henwood, S.Tsemberis. [3] National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report (2014), Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada, Goering, S. Veldhuizen, A. Watson, C. Adair, B. Kopp, E. Latimer, G.Nelson, E. MacNaughton, D.Streiner, T. Aubry. [4] Source Localtis.

Target

Straying from the initial Housing First model, we intend to generalize the Housing First approach to the whole homeless population who is denied access to independent, long-term housing, and not only the homeless population with the most complex needs (50, 000 households). This approach is a “housing led” shift in the way homelessness is dealt with.

Aim